Looking at that herringbone countertop never gets old. I built it for my sister in law, and sometimes I’ll FaceTime her just so I can catch a glimpse of it in the background. She’s uses the herringbone countertop as a place TO SET THINGS, if you can believe it. I just have to keep repeating in my head “the function of design is letting the design function”…ugh.

his post includes affiliate links. If you purchase from these links, I may get a small commission from the seller. But the great thing is, this doesn’t cost you any extra money!

SUPPLIES

- (1) 3/4 x 48 x 96 inch Sheets of Sande Plywood (# of boards to purchase is dependent on size of countertop)

- (1) 1 x 2 x 96 inch Select Pine

- 1 1/4 inch Brad Nails

- 150 Grit Orbital Sandpaper

- Stain color of your choice – I used Early American by Varathane

- Clamps

- Lint Free Rags

- Silicone Caulk

- Epoxy

- High Quality Paintbrush

- Notched Trowel

- Painters Tape

- Plastic Drop Cloths

TOOLS

Welcome or Welcome Back!

If you’re reading this post because you’re interested in building a herringbone countertop and want to check out how I made mine, welcome! If you’re reading this post because you’ve started to build a Butler’s Pantry and are ready for the next step, welcome back!

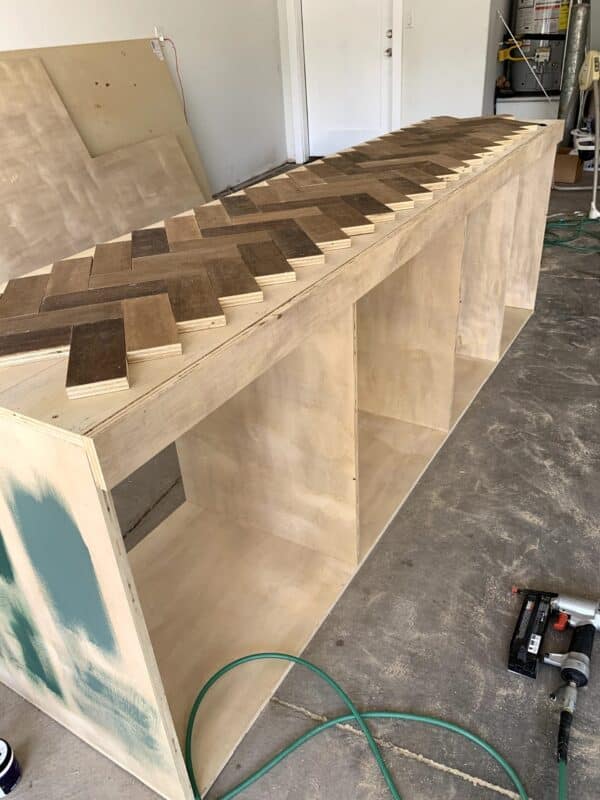

I’m building my counter on top of this 19 3/4 x 66 1/4 inch piece of sande plywood.

How to Turn Plywood into Herringbone Boards

After some calculations, I found that 3 x 8 inch pieces of plywood would allow for three full boards in the middle, and about 1/2 of a board on each side.

I used my table saw to rip the plywood into 3 inch strips.

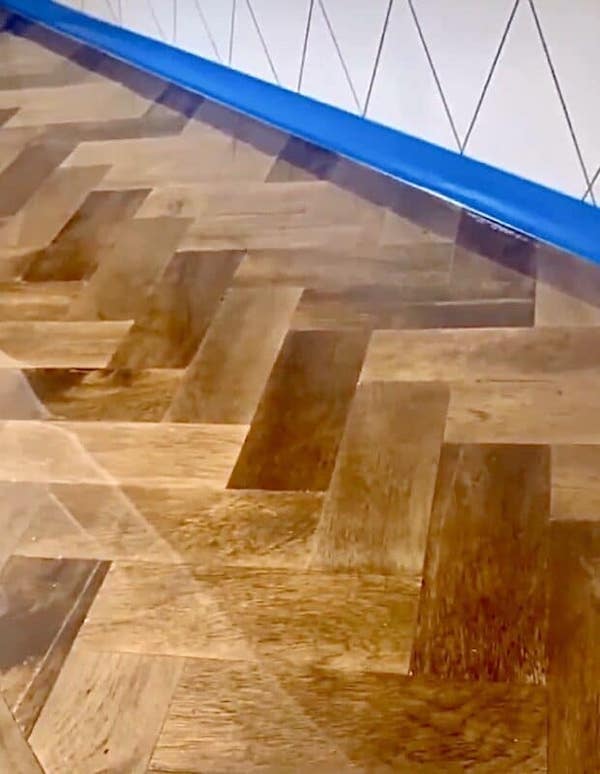

The countertop in my inspiration picture had several different shades of wood, and so I figured out a staining combination that would achieve that type of look. I always like to sand my wood before I apply a stain, so I used my orbital sander with 150 grit sandpaper and gave the wood a quick passover, being careful not to sand away any of the veneer on top of the plywood.

I divided the strips into three equal piles. On one pile, I applied two heavy coats of stain, always making sure I wiped with the grain of the wood. The second pile received one light coat of stain. For the third pile, I sprayed water onto the strip, wiped it off, and applied a light coat of stain. The water prevented the wood from absorbing too much of the stain.

I clamped a piece of wood onto the fence of my miter saw to act as a “stop”. When the strips were butted up to the stop, I was able to quickly cut them into 8 inch pieces, as well as ensure each consecutive piece would be the same length. The success of the pattern depends of every board being exactly the same size.

How to Place the Herringbone Boards

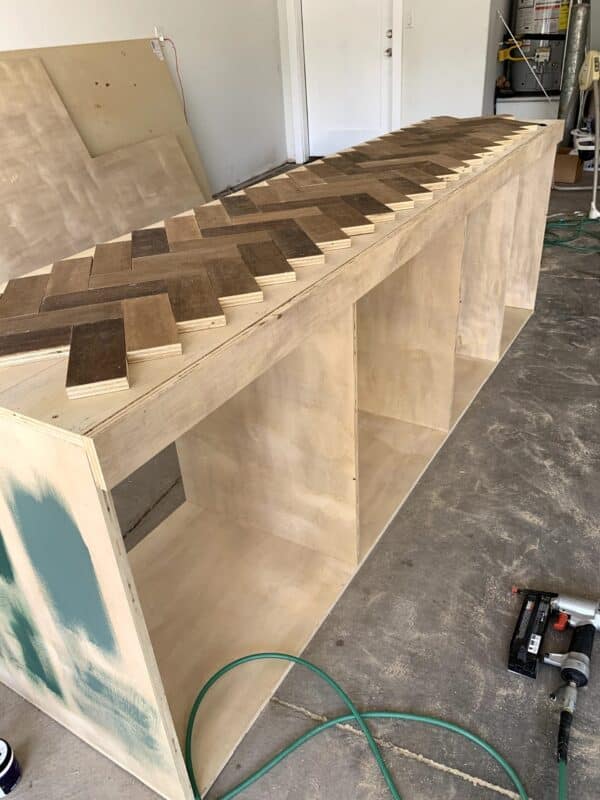

Next, I started working on the herringbone pattern by placing three boards together down the length of the cabinet, into a color pattern I thought looked natural.

Once I was happy with the arrangement, I nailed the end of each board into the top of the cabinet to secure it in place, making sure the boards were super tight against each other to prevent gaps.

I added the remaining boards to cover the rest of the cabinet top, making sure the boards on each side jutted out past the top of the cabinet. Those were placed super tight against each other and nailed into the top of the cabinet.

How to Trim the Herringbone Wood

My plan was to add a face frame to the entire pantry, and so I had already secured a 3 1/2 x 66 1/4 inch piece of select pine onto the cabinet face to hang down in the front, visible in the picture below:

I used a piece of baseboard to act as a straight edge to draw a line on the herringbone where I needed to trim off the overhang. Then I ran my circular saw along the line, without a guide.

I had a 1 1/2 x 66 1/4 inch piece of select pine ready to use as a “flush tester”, which I’ll explain.

When I was done cutting the boards, I nailed my flush tester board onto the cabinet with just a few nails. I got an F on my flush test.

The line I had drawn was not straight, nor was my cut.

It was a very sad moment. On the left in the picture below, you can see how uneven the cut is against my flush test board, resulting in a decently sized gap.

Had I been successful, it would have looked like this, minus the cartoon aspect:

I had to pop off the flush tester board as well as the poorly cut herringbone boards, and replace them with new pieces of cut and stained boards for attempt number two.

What I ended up doing was using a clamp to secure a 2 x 4 to the countertop, and use that as a guide for my circular saw to follow along the length. Any type of long, factory made straight edge would have worked. I frequently double checked that my cut was still straight, and adjusted the clamps as necessary.

Other than just a few tiny gaps here and there, it was pretty dang close to perfect. Probably a B+.

I stained the flush tester piece to match the countertop, and nailed it on top of the front framing board so it sat flush with the newly cut herringbone pieces. how to build a herringbone countertop

I brought the whole cabinet inside the pantry, secured it to the base, and added all the face frame pieces. If you’d like to see how I did that, check out the rest of my Butler’s Pantry tutorial.

One Last Stain Check

Before I committed to applying the epoxy, I took one last look at the color gradient in my countertop and decided there were a few boards that were just a little too light. I applied additional stain to those boards because if not, those lighter, offensive boards would be the ONLY thing I noticed for the rest of the countertop’s life.

How to Fill the Gaps with Caulk to build a herringbone countertop

The counter didn’t look right just sitting up against the wall, so I added shoe molding to the sides and back to cover the crack, and secured it with brad nails. Shoe molding is a tiny, angled piece of wood that fills that awkward crack and hides places where the wall might not be straight. I caulked it with latex caulk and let that dry. Then I taped off the wall and counter very well, and painted it white.

Before I poured the epoxy coating, I had to fill in all the little gaps along the wood pieces because I didn’t want epoxy seeping into the seams. The entire tiny gap between my herringbone and the newly stained tester piece was caulked because if epoxy seeped into that crack, it would end up draining all of my epoxy onto the floor.

I pressed clear silicone caulk into the seams, and wiped it off with a wet rag. The caulk went on white but dried clear.

How to Epoxy a Countertopow to build a herringbone countertop

I could write an entire book on how to use epoxy.

So I did, right here.

I’ve used it several times, and have learned a lot of tricks, and have had a lot of fails. I decided to compile step by step instructions on how to successfully use epoxy. It includes the exact products I used, why I chose those products, and how to care for epoxy countertops.

It also includes very a thorough tutorial on how to create a faux marble countertop, which is then protected by the epoxy, creating the beauty of marble without the high cost.

If you choose to forgo epoxy, you could seal the counter with several coats of polycrylic. I wanted a durable coating that would withstand the abuse of my sister in law’s kitchen-aid, so epoxy was the best choice.

If you’d like to know everything there is to know about applying epoxy to granite, laminate, mdf, and wood, check out my E-book.

This is the How to build a Butler’s Pantry Part 1 where I explain how to build the cabinets, and in the Butler’s Pantry Build Part 2, I explain how to do all the frame and finish work.

These are the floating shelves I built for all the appliances that need quick access.

Do you like the wallpaper design you see in the pictures? I did that with a sharpie!

And lastly, if you’re a visual learner, all of my stories for my projects can be found in my highlights on my instagram account @crystelmontenegrohome.